Overpopulation in India.

The Transmission of the Coronavirus is linked to high Urban Population Densities

In 1898, the British Colonial authorities created the Bombay Improvement Trust on the heels of a devastating plague.” wrote Vaishinavie Chankdra shekhar & Clara Lewis in a recent edition of the “Times of India”.

This improvement Trust opened up congested neighbourhoods, built housing for workers and laid down strict rules for ventilation and sanitation. Their measures were supposed to shape the modern Bombay.

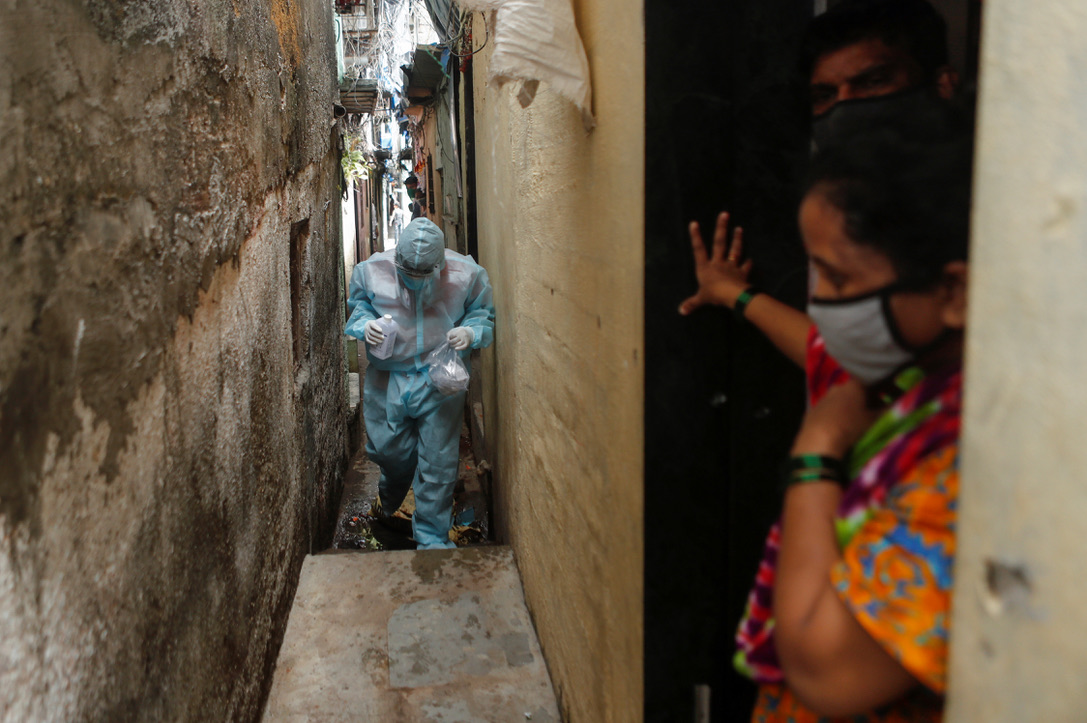

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic it is clear that the lessons of the last pandemic have been long forgotten. Most of the slum inhabitants here are still living in Dickensian conditions not dissimilar to the 1890’s.

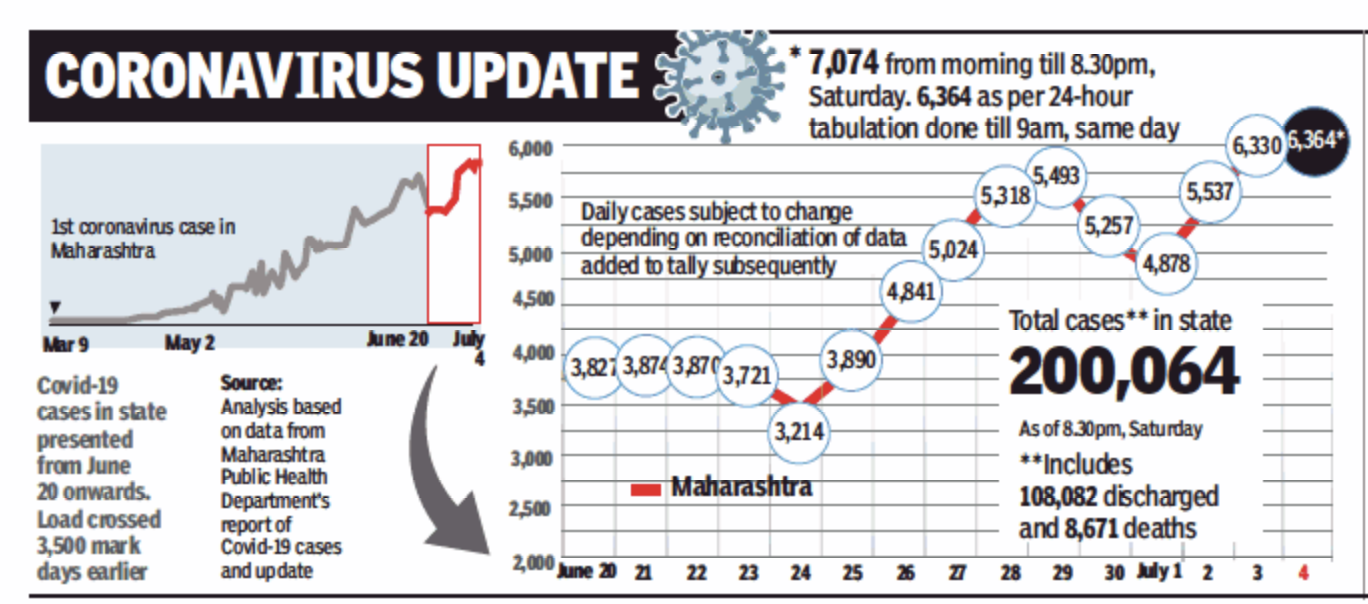

Times of India Chart showing the monthly change in Covid-19 cases in Maharashtra

At the beginning of the outbreak some of the hospitals were not prepared for the surge in the influx of patients and there were horror stories circulating in the media about people sharing beds so that they could use the same oxygen cylinders, wards stinking of urine from un-emptied bedpans, and patients being treated next to corpses because the morgues were unable to cope with the huge increase in death rate. Fortunately, this situation has now greatly improved. Nightingale hospitals have been set up in every available large building, sports hall or other suitable location in the city and the Government are trying to cope as best they

The Government had initially completely underestimated the challenges of dealing with the millions of unemployed at the outbreak of the pandemic. The migrant day workers who form the bulk of the labor force suddenly found themselves without an income to pay for neither food or rent. The announcement of a the lockdown created a panic mass movement of people back to their villages which are quite often situated in remote and distant parts of the country.

On March 26th The Indian Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a INR 1.7 trillion (~USD 22 billion) relief package. However money takes time to reach its target and many people who were already under severe stress could not access this relief for an extended period of time. Some Indian States issued relief aid earlier on in March. For instance, the Upper Pradesh government issued RS 1,000 (about $13) to 3.5 million directly into the bank accounts of migrant workers and gave them access to daily food rations

Then on the 30th June the Prime minister Nirendra Modi announced the worlds biggest relief package by extending the Government (PMGKAY) relief program of free rations to 800 million, mostly poor, people until the end of November.

Migrant and Unemployed workers Queue for Food rations.

The only Mumbai inhabitants who are content are those residents who normally live under the flight path of the Aeroplanes near Mumbai Airport. They can now live in tranquil silence.

It is now just a few days since the Government lifted the 2 km lock-down and travel restrictions. The Mumbai population can now circulate more freely through the city although people are supposed to abide by the social distancing rules. Businesses are now beginning to open again and the age old traffic congestion problem is slowly beginning to return.

The Times of India newspaper pours out a continuous rendition of articles damming the Government for its incessant failure to deal with the Mumbai’s shocking living conditions in the slums. This begs the questions as to what can be and will be done to change things for the better when the Pandemic is over.

One solution is for the Government to implement a plan to build lots more affordable housing stock in Mumbai.

The Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) which was set up in 1997 to build modern housing stock and rid Mumbai of the slums has failed to deliver. Since that time only 2 hundred thousand homes have been built.

Public housing, sanitation and health infrastructure for the poor has remained stagnant for decades. Despite high profile programs, there is a 100,000 shortfall in public toilets and an estimated staggering shortfall of 1.1 million affordable houses.

.

A panel of doctors set up recently under the authorization of the State Home Minister Jitendra Ahwad in order to offer key deliverable to the inhabitants of the slum areas during the COVID-19 pandemic concluded that it would take 250 years to clear the slums at the current rate of construction.

Unless the underlying reasons for the migration of rural Indians to its towns and cities can be solved then the situation in the city slums is likely to worsen.

It will need a herculean effort to change the current way of thinking. The route of the problem is the population explosion over the last century.

Although India was the first country in the world to adopt a family planning programme as far back as in 1952, the population of this country is still a long way from achieving population stabilisation. Everyone in India continuously comments on the problem of Indian overpopulation but they are uncertain as to how population stabilisation can be achieved.

India’s population is still growing by 15.5 million a year and if this trend continues India may overtake China in 2045 by reaching a population of 1.5 billion. India needs to get a grip on this issue. More than half of India’s governing bodies comprising of twenty eight States and eight Union Territories have fertility rates higher than replacement level.

Narendra Modi is highly aware of the problem of the Indian population explosion. In his 2019 Independence Day Speech he urged Indians who had children to keep their families small.

Let us hope that his words can be translated into action. Population should be a number one issue in India.

The second reason why people flock to the cities like Mumbai is because there is the lack of job opportunities and impoverished lifestyle for the 600 million rural Indians. During this Global COVID-19 pandemic there must be very few people who haven’t now understood the momentous advantages of the internet. It has kept us all in contact with each other and a brought real sense of communication. The internet is a source of education, communication and the most powerful tool for marketing and research. This will continue to change the face of India going forward.

None of this technology can be sustained without power, lots of it, and hopefully in future in the form of renewable energy. Electrification in India has made considerable progress. Between 2000 and 2016, half a billion people gained access to electricity in India, increasing the share of grid-electrified households from 43% to 82%. Since then, several new efforts are underway at central state levels, with the goal of achieving universal household electrification by 2030.

A report published in 2019 funded by the Rockefeller Foundation on the “Electrification of India” concluded that the take up of electricity is still hampered by affordability, continued power cuts, billing in-efficiency, inflated electricity bills, and high connection costs. In fact one in two grid users faces a power cut of at least 8 hours daily.

This pandemic might have dealt India a hard blow by blunting its plans to accelerated development and its aspirations to raise the standard of living for its people.

The consequences of all this fall in growth as a result of the corona virus is hard to comprehend. Readers of this report should feel very lucky if they live in a safe, well-endowed location.

Appreciation to the following: I would like to thank the “Times of India” and the “Economic Times” of India for their help with newspaper articles and photos which were contributed to this blog.

2 comments

MR DAVID R RCHARDSON

July 29, 2020 at 2:02 pmTest

MR DAVID R RCHARDSON

July 29, 2020 at 2:03 pmTest Reply